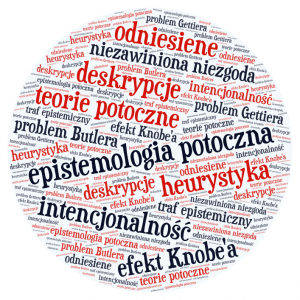

Seminarium poświęcone jest problematyce epistemologii potocznej w filozofii eksperymentalnej, tj. dziedzinie badań filozoficznych, w której podejmowane są systematyczne studia empiryczne na temat potocznych intuicji w kwestiach ważnych dla filozofii (np. na temat wiedzy lub uzasadnienia przekonań).

Prowadzący: Katarzyna Kuś, Adrian Ziółkowski

BLOK I – Epistemologia potoczna w kontekście filozofii eksperymentalnej i psychologii potocznej

- Kitchener R. F. (2002) Folk epistemology: An introduction, „New ideas in Psychology” 20(2), 89-105.

- Hardy-Vallée Benoit, Dubreuil Benoît (2010) Folk epistemology as normative social cognition, „Review of Philosophy and Psychology” 1(4), 483-498.

- Nadelhoffer T., Nahmias E. (2007) The past and future of experimental philosophy, „Philosophical Explorations” 10, 123-149.

- Andow J. (2016) Thin, fine and with sensitivity: a metamethodology of intuitions, „Review of Philosophy and Psychology” 7(1), 105-125.

BLOK II – Intuicje potoczne dotyczące przypadków Gettierowskich

- Weinberg J. M., Nichols S., Stich S. (2001) Normativity and epistemic intuitions, „Philosophical Topics” 29(1-2), 429-460.

- Seyedsayamdost H. (2015) On Normativity and Epistemic Intuitions: Failure of Replication, „Episteme” 12 (1), 95-116.

- Kim M., Yuan Y. (2015) No Cross-Cultural Differences in the Gettier Car Case Intuition: A Replication study of Weinberg et al. 2001, „Episteme” 12(3), 355-361.

- Starmans, C., Friedman, O. (2012) The folk conception of knowledge, „Cognition” 124(3), 272-283.

- Nagel, J., San Juan, V. & Mar, R. (2013) Authentic Gettier Cases: a reply to Starmans and Friedman. Cognition 129 (3):666-669.

- Machery E., Stic, S., Rose D., Chatterjee A., Karasawa K., Struchiner N., Sirker S., Usui N., Hashimoto T. (2015) Gettier Across Cultures. „Noûs” 50(4), DOI: 10.1111/nous.12110.

BLOK III – Kontekstualizm epistemiczny i intuicje potoczne

- Feltz A., Zarpentine C. (2010) Do You Know More When it Matters Less?, „Philosophical Psychology” 23(5), 683-706.

- May J., Sinnott-Armstrong W., Hull J. G., Zimmerman A. (2010) Practical Interests, Relevant Alternatives, and Knowledge Attributions: An Empirical Study, „Review of Philosophy and Psychology” 1, 265-273.

- Hansen N., Chemla E. (2013) Experimenting on contextualism., „Mind and Language” 28(3), s. 286-321.

- Sripada C. S., Stanley J. (2012) Empirical tests of interest-relative invariantism, „Episteme” 9(1), 3-26.

- Buckwalter W., Schaffer J. (2015) Knowledge, Stakes, and Mistakes. „Noûs” 49(2), 201-234.

BLOK IV – Wiedza i normy asercji

- Turri J. (2013) The test of truth: An experimental investigation of the norm of assertion. „Cognition” 129(2), 279-291.

- Turri J. (2015). Knowledge and the norm of assertion: a simple test. Synthese” 192(2), 385-392.

- Turri J. (2015), Selfless assertions: some empirical evidence. „Synthese” 192(4), 1221-1233.

- Reuter K., Brossel P. (2017) No Knowledge Required, manuskrypt

BLOK V – Niestandardowe czynniki wpływające na atrybucje wiedzy

- Beebe J. R., Jensen M. (2012) Surprising connections between knowledge and action: The robustness of the epistemic side-effect effect. „Philosophical Psychology” 25(5), 689-715.

- Beebe J. R, Shea J. (2013) Gettierized Knobe effects. „Episteme” 10(3), 219-240.

- Buckwalter W. (2014). Factive Verbs and Protagonist Projection. „Episteme” 11(4), 391-409.

- Buckwalter W., Stich S (2013) Gender and philosophical intuition [w:] Knobe J., Nichols S. (red.) „Experimental Philosophy: Volume 2”, Oxford University Press.